By NICHOLAS KULISH

BERLIN — To judge by the outpouring of comments from politicians and writers and from the newspaper and magazine articles in response to the Nobel laureate Günter Grass’s poem criticizing Israel’s aggressive posture toward Iran, it would appear that the public had resoundingly rejected his work.

But even a quick dip into the comments left by readers on various Web sites reveals quite another reality.

Mr. Grass has struck a nerve with the broader public, articulating frustrations with Israel here in Germany that are frequently expressed in private but rarely in public, where the discourse is checked by the lingering presence of the past. What might have remained at the family dinner table or the local bar a generation ago is today on full display, not only in Mr. Grass’s poem, but on Web forums and in Facebook groups.

One word has surfaced consistently in such discussions: “keule,” which means club or cudgel. The charge of anti-Semitism aimed at Israel’s critics — and in the case of Mr. Grass, by bringing up his past as a member of the Waffen-SS — is widely viewed as a blunt instrument that silences debate, and in the process prevents Mr. Grass from making a point about the dangers of a first strike by Israel against Iran over its disputed nuclear program.

“Every time you speak out and say something that isn’t superpolitically correct, there is a 99 percent chance that you are regarded as right wing,” said Moritz Eggert, a composer based in Munich. Mr. Eggert posted his own musical interpretation of Mr. Grass’s poem with simplified lyrics on YouTube. “Israel, I love you, but don’t attack Iran,” he sings.

Mr. Eggert said he was trying to skewer both sides in the debate. While he said he did not like Mr. Grass’s poem, “it’s embarrassing the way the intellectuals try to paint him in the worst light possible.”

Mr. Grass’s critics hail mostly from the cultural and political elite, while his support appears to be far more broadly based — even if Mr. Grass is not himself seen as the best spokesman for that view, given his own Nazi past.

“The published opinions are all coming from the usual suspects,” said Claus Stephan Schlangen, one of the people behind a Facebook group formed in support of Mr. Grass’s poem. “People just don’t believe what the media is selling anymore.”

Mr. Schlangen is helping run a Facebook page called “Support Günter Grass — What Must Be Said.” The name is based on the title of the 69-line poem, which was published in the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung last week. In the poem, Mr. Grass, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1999 and the author of the famous World War II novel “The Tin Drum,” said that Israel was a threat to world peace because of its warnings that it might attack Iran over its nuclear program.

The group’s page, which had more than 3,500 Facebook “likes” as of Thursday evening, shows a dove and Mr. Grass with his trademark pipe superimposed over the colors of the rainbow. “We say no to a war of aggression against Iran,” the text reads. Mr. Schlangen said that he and the site’s other manager policed the comments for anti-Semitic remarks, but that they just as often removed threatening language from Israel’s supporters.

Mr. Schlangen said he understood that the condemnation of Mr. Grass was about “German sensitivities and German history,” but he argued that “our mandate is not to support Israel whatever it does, but instead to fight injustice wherever it appears, which can also be in Israel.”

The Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, personally rebuked Mr. Grass over the poem, and the interior minister declared Mr. Grass to be unwelcome in Israel and barred him from entering the country. On Thursday, Mr. Grass, who seems to be reveling in the attention, waded back into the fray, this time in prose instead of verse, writing an article in the Süddeutsche Zeitung that compared Israel to Myanmar and the former East Germany, the only other countries that have forbidden him entry.

Sharp criticism of Israel, particularly from the left, has long been a tradition among European intellectuals, and Mr. Grass’s poem caused little stir on the Continent outside of Germany. But political and scholarly elites here have more often resisted that trend, tending to see basic support for Israel as a German responsibility, if not a necessity, after the Holocaust.

But the public response to the furor over Mr. Grass’s poem suggests that that attitude is breaking down as World War II recedes into history. “In the populism you see surfacing on a large scale, the public is all behind Grass,” said Georg Diez, an author and journalist at the magazine Der Spiegel who has written critically of the poem.

More than a week after the publication of “What Must Be Said,” it was still the subject of significant discussion. In the Thursday issue of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung newspaper, another critical commentary appeared, this time with the headline “He Is the Preacher With the Wooden Mallet.” And on Thursday night, the talk show host Maybrit Illner held yet another televised discussion, “Grass in the Pillory: Is Criticizing Israel Really Taboo?”

Germany has come a long way since World War II in its struggle to become an ordinary country. The Berlin Wall is gone, and east and west are unified. The country recently ended conscription, which was intended to force a break with the country’s militaristic past and provide a direct link between the military and society as a whole.

But the subject of Jews and the Holocaust remain fraught topics even today.

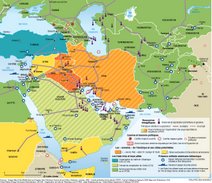

In Germany, as elsewhere in Europe and in the United States, the conflict with the Palestinians has earned Israel its share of detractors. And for Germans who internalized pacifism as the most important lesson of World War II, the aggressive language that Israel has directed at Iran has seemed alarming.

Peace activists in particular have rushed to Mr. Grass’s defense, saying they were glad that he had brought the subject of a first strike by Israel into the public discourse. “His voice carries significant weight here,” said Manfred Stenner, director of the German Peace Network in Bonn. “We have been saying for a long time that a political solution has to be found.”

Ze’ev Avrahami, an Israeli journalist and restaurateur in Berlin who has written about the Grass controversy for the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, said that he had left Israel because he could not support his country’s policies in the West Bank and Gaza. But he said that he and Israeli workers at his restaurant, Sababa, in the chic Prenzlauer Berg neighborhood, have found the tone of the discussions disquieting.

“They are not allowed to say anything about Jewish people, and they will never say anything about Jewish people, but to say everything about Israel is O.K.,” Mr. Avrahami said. “It’s absolutely the new anti-Zionism for all....”

“Israel has earned criticism,” he said, and “on this level....”

Maxim Biller, a German writer and commentator who is Jewish, welcomed the more open debate. “Is it better to keep the lions in their cages, or does it make the lions more and more furious that one day they will jump out of their cages and do their thing?” Mr. Biller asked. “Maybe it’s very good that from time to time one of these old men opens his mouth, says something like this, and then people discuss it.”

“As a potential target of these people,” he said, “I’m quite happy that the elite is still defending some clear positions.”