A rare voice of courage: journalist Gideon Levy

Gideon Levy (Haim Taragan/Haaretz)

Gideon Levy is a rare voice of courage in an Israeli media generally

supine towards the political establishment. Since 1988, he has written

the "Twilight Zone" column for the Israeli daily Haaretz, documenting

unflinchingly the myriad cruelties inflicted on the Palestinian people

under occupation. In his new book Gaza, a collection of articles which

has just been published in French, Levy utters phrases that, by his

own admission, are considered "insane" by most of his compatriots. The

Electronic Intifada contributor David Cronin spoke with Gideon Levy

about his background and journalism.

David Cronin: You were born in Tel Aviv in the 1950s. Were your

parents survivors of the Holocaust?

Gideon Levy: They were not Holocaust survivors, they just left Europe

in 1939. My father was from Germany, my mother Czech. Both were really

typical refugees because my father came on an illegal ship, which was

stopped for half a year in Beirut by the British and only after half a

year on the ocean could it make it to Palestine. My mother came on a

project with Save the Children. She came without her parents directly

to a kibbutz.

My father always said he never found his place in Israel. He lived

there for 60 years but his life was ruined. He had a PhD in law but

never practiced it in Israel. He never really spoke proper Hebrew. I

think he was really traumatized all his life.

At the same time, he never wanted to go back [to Europe] even for a

visit. He came from Sudetenland, which became Czechoslovakia. All the

Germans were expelled.

DC: How did your parents' history affect you when you were growing up?

GL: I was a typical first-generation immigrant. When my mother used to

talk to me in German, I was so ashamed that she spoke to me in a

foreign language. Her name was Thea; I always said it was Lea. Thea is

a Greek name from mythology. It is a beautiful name but as a child I

always said Lea just to cover up the fact they were immigrants.

My father's family name was Loewy and for so many years I was called

Loewy. But then I changed it to Levy and now I regret it so much.

DC: Tell me about your military service in the Israeli army.

GL: I did my military service in the [army's] radio station. I was

always a good Tel Aviv boy; I had mainstream views; I was not brought

up in a political home.

I was at the radio station for four years instead of three [the

standard length of military service] but for the fourth year as a

civilian. It's a very popular radio station; the army finances it but

it is totally civilian.

I was totally blind to the occupation. It was a word I didn't dare to

pronounce. I was a typical product of the Israeli brainwash system,

without any doubts or questions. I had a lot of national pride; we are

the best.

I remember my first trip to the occupied territories [the West Bank

and Gaza Strip]. There were a lot of national emotions visiting

Rachel's Tomb and the mosque in Hebron. I didn't see any Palestinians

then; I just remember the white sheets on the terraces. I was even

convinced that they were happy we had conquered them, that they were

so grateful we released the Palestinians from the Jordanian regime.

DC: What was the turning point that caused you to criticize the

occupation?

GL: There was no turning point. It was a gradual process. It started

when I started to travel to the occupied territories as a journalist

for Haaretz. It is not as if I decided one day, "I have to cover the

occupation." Not at all. I was attracted gradually like a butterfly to

a fire or to a light.

My political views were shaped throughout the years; it's not that

there was one day that I changed. It was really a gradual process in

which I realized this is the biggest drama: Zionism, the occupation.

And at the same time I realized there was no one to tell it to the

Israelis. I always brought exclusive stories because almost nobody was

there. In the first [Palestinian] intifada, there was more interest in

the Israeli media. But between the first intifada and the second

intifada, I really found myself almost alone in covering the

Palestinian side.

DC: Have you completely rejected Zionism?

GL: Zionism has many meanings. For sure, the common concept of Zionism

includes the occupation, includes the perception that Jews have more

rights in Palestine than anyone else, that the Jewish people are the

chosen people, that there can't be equality between Jews and Arabs,

Jews and Palestinians. All those beliefs which are very basic in

current Zionism, I can't share them. In this sense, I can define

myself as an anti-Zionist.

On the other hand, the belief about the Jewish people having the right

to live in Palestine side by side with the Palestinians, doing

anything possible to compensate the Palestinians for the terrible

tragedy that they went through in 1948, this can also be called the

Zionist belief. In this case, I share those views.

DC: If somebody was to call you a moderate Zionist would you have any

objections?

GL: The moderate Zionists are like the Zionist left in Israel, which I

can't stand. Meretz and Peace Now, who are not ready, for example, to

open the "1948 file" and to understand that until we solve this,

nothing will be solved. Those are the moderate Zionists. In this case,

I prefer the right-wingers.

DC: The right-wingers are more honest?

GL: Exactly.

DC: As an Israeli Jew, have you encountered hostility from

Palestinians during your work in the Occupied Palestinian Territories?

GL: Never. And this is unbelievable. I've been traveling there for 25

years now. I've been to [the scene of] most of the biggest tragedies

one day after they happened. There were people who lost five children,

seven children in one case.

I was always there the morning after and I would have appreciated if

they told me, "Listen we don't want to talk to an Israeli, go away."

Or if they would tell me: "You are as guilty as much as any other

Israeli." No, there was always an openness to tell the story. There

was this naive belief or hope that if they tell it to the Israelis

through me, the Israelis will change, that one story in the Israeli

media might also help them.

They don't know who I am. The grassroots have never heard about me;

it's not like I have a name there. The only time we were shot in our

car was by Israeli soldiers. That was in the summer 2003. We were

traveling with a yellow-plate taxi, an Israeli taxi: bullet-proof,

otherwise I wouldn't be here now. It was very clear it was an Israeli

taxi. We were following a curfew instruction. An officer told us: "You

can go through this road." And when we went onto this road, they shot

us. I don't think they knew who we were. They were shooting us as they

would shoot anyone else. They were trigger-happy, as they always are.

It was like having a cigarette. They didn't shoot just one bullet. The

whole car was full of bullets.

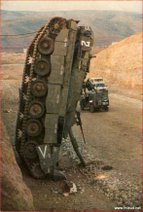

DC: Have you been in Gaza recently?

GL: I have been prevented from going there. The last time I was there

was in November 2006. As I mention in the foreword of my book, I was

visiting the Indira Gandhi kindergarten in Gaza the day after a nurse

[Najwa Khalif], the teacher in the kindergarten, was killed in front

of all her children [by an Israeli missile]. When I came in, they were

drawing dead bodies, with airplanes in the sky and a tank on the

ground. I just went to the funeral of the nurse. It was called the

Indira Gandhi kindergarten not because [assassinated Indian prime

minister] Indira Gandhi was involved but because the owner of this

kindergarten was named Indira Gandhi as an appreciation of Indira

Gandhi.

DC: You have often talked about how you enjoy complete freedom to

write anything you wish. But do you get the impression that life is

getting more difficult for people with critical voices in Israel and

that the government is actively trying to stifle dissent?

GL: Me personally, writing for Haaretz, appearing on TV, practically I

have never gained such freedom. I'm appearing every week on Israeli TV

on a discussion program. There were years in which I had to be more

cautious, there were years in which the words "crimes of war" were

illegal, even in Haaretz. Today, those words are over and I'm totally,

totally free. No pressure from government or army -- nothing.

But for sure, in the last year there have been real cracks in the

democratic system of Israel. [The authorities have been] trying to

stop demonstrators from getting to Bilin [a West Bank village, scene

of frequent protests against Israel's wall]. But there's also a

process of delegitimizing all kinds of groups and [nongovernmental

organizations] and really to silence many voices. It's systematic --

it's not here and there. Things are becoming much harder. They did it

to "Breaking the Silence" [a group of soldiers critical of the

occupation] in a very ugly but very effective way. Breaking the

Silence can hardly raise its voice any more. And they did it also to

many other organizations, including the International Solidarity

Movement, which are described in Israel as enemies.

DC: Did you ever meet Rachel Corrie, the American peace activist

killed by an Israeli bulldozer seven years ago?

GL: I never met her, unfortunately. I just watched the film about her

last week. Rachel, James Miller and Tom Hurndall were all killed

within six or seven weeks, one after the other, in the same place in

Gaza, more or less. It was very clear this was a message.

DC: What do you think of her parents' decision to sue the State of

Israel over her killing?

GL: Wonderful. I saw them both when they were in Israel. They are

really so noble. They speak about the tragedy of the soldier who

killed their daughter, that he is also a victim. And they are so low-

key. I admire the way they are handling it and I hope they will win.

They deserve compensation, apologies, anything. Their daughter was

murdered.

I participated in a film about James Miller, a documentary by the BBC.

James Miller's story is even more heart-breaking. There was a real

murder. They knew he was a journalist, he was a photographer, he had

his vest saying "Press." It was very clear he was a journalist. And

they just shot him.

DC: How do you feel about Israel's so-called insult toward the US,

when it announced the construction of new settlements in East

Jerusalem during a visit to the Middle East by US Vice President Joe

Biden?

GL: I really think it is too early to judge. Something is happening.

For sure, there is a change in the atmosphere. For sure, [Israeli

Prime Minister Benjamin] Netanyahu is sweating. And the question is:

do the Americans have a clear program?

One thing must be clear: Israel has never depended so much on the

United States like it does today. Until now [Barack] Obama has made

all the possible mistakes. His first year was wasted. But still we

have to give them [the Americans] a chance because for sure there is a

change in the tone. But I'm afraid their main goal now is to get rid

of Netanyahu. And if this is the case, it will not lead anywhere.

Anyone who will replace him will be more of the same, just nicer. It

will be again this masquerade of peace process, of photo

opportunities, of niceties which don't lead anywhere. From this point

of view, I prefer a right-wing government. At least, what you see is

what you get.

DC: Spain, the current holder of the European Union's (EU) rotating

presidency, appears keen to strengthen the EU's relationship with

Israel. What signal would deeper integration of Israel into the EU's

political and economic programs send?

GL: I think it would be shameful to reward Israel now. To reward it

for what? For building more settlements? But I think also that Europe

will follow changes in Washington like it follows almost blindly

anything the Americans do.

DC: There was a minor controversy recently about the fact that Ethan

Bronner, The New York Times' correspondent in Jerusalem, has a son in

the Israeli army. Do you have any children in the army and do you

think that Bronner was compromised by this matter?

GL: My son is serving in the army. My son doesn't serve in the

territories but I have always disconnected myself from my sons. They

have their own lives and I haven't tried to influence them.

About Ethan Bronner, it's really a very delicate question. The fact

there are so many Jewish reporters, Zionist reporters who report for

their national media from the Middle East, for sure is a problem. On

the other hand, I know from my own experience, you can have a son

serving in the army and be very critical yourself. I wouldn't make

this a reason for not letting him cover the Middle East for The New

York Times, even though I must tell you that I don't see the

possibility where The New York Times' correspondent in Jerusalem is

someone whose son is serving in the [Palestinian resistance

organization] al-Aqsa Brigades, for example.

DC: What role can journalists play in trying to achieve a just and

lasting solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?

GL: There is an enormous historic role that the Israeli media is

playing. The Israeli media, which is a free media, free of censorship,

free of governmental pressure, has been dehumanizing the Palestinians,

demonizing them. Without the cooperation of the Israeli media, the

occupation would not have lasted so long. It is destructive in ways I

cannot even describe. It's not Romania, it's not Soviet Russia. It's a

free democracy, the media could play any role but it has chosen to

play this role. The main thing is about the flow of information. It is

so one-sided, so much propaganda and lies and ignorance.

The French-language edition of Gideon Levy's book Gaza: Articles pour

Haaretz, 2006-2009, is published by La Fabrique. An English edition

will be available soon.

David Cronin's book Europe's Alliance with Israel: Aiding the

Occupation will be published later this year by Pluto Press.