Rent-a-soldiers want to stay in business

http://mondediplo.com/2010/02/08afghanistan

A worrying two-thirds of the Pentagon’s personnel in Afghanistan are private military contractors, unaccountable to military law or ethics, swaggeringly overbearing, and not in any hurry to help improve the poor security situation that assures their firms’ current and future profits

by Marie-Dominique Charlier

The Central Intelligence Agency hired staff from a private military company called Blackwater in 2004 as part of a secret programme to track down and assassinate al-Qaida leaders, according to the New York Times of 19 August 2009. The paper’s sources among current and former US government officials said that Blackwater had helped the CIA with planning, training and surveillance, for which it had charged several million dollars, but the programme had failed to capture or assassinate a single al-Qaida figure.

Blackwater changed its name to Xe Services following the controversy over its role in Iraq. Five of its guards escorting a US State Department convoy through Baghdad on 16 September 2007 were accused of shooting civilians in al-Nousour Square, killing 14 (the US count) or 17 (the Iraqi count). In spite of this blunder, and many others, the contractors headed for Afghanistan, where they have continued in the same manner. (The case against them was dismissed on 31 December 2009 owing to procedural errors; the US Department of Justice has decided to appeal against the decision.) On 5 May 2009 four employees of Blackwater/Xe (operating under the name Paravant) reportedly shot at a car in Kabul, killing at least one person and wounding four. On 7 January federal prosecutors in the US announced that two of the Xe employees had been charged with killing two Afghan men and wounding another. The opacity of their employment contracts has not allowed them to escape prosecution.

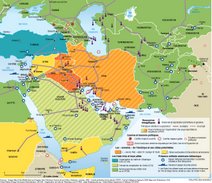

Private military companies (PMCs) (1) have evolved rapidly since they first appeared in the 1990s and now play a key military and economic role in armed conflicts. The global market for private military services is worth more than $100bn a year. This growth has been encouraged by drastic cuts in US army manpower at the end of the cold war and the decision under Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld (2001-06) to “rationalise” defence spending by outsourcing many of the not specifically military functions to the private sector. The aim was to circumvent Congress control and US public opinion, and also to allow greater flexibility in hiring contractors for clandestine operations.

High numbers

Estimates of the numbers of PMC personnel in Afghanistan vary from 130,000 to 160,000 (2), the second-largest deployment after Iraq (3), which it is set to overtake in the near future. The 30,000 extra US troops bound for Afghanistan could be accompanied by up to 56,000 additional contractor personnel. PMC contractors will then account for nearly two-thirds of all the Pentagon’s personnel in Afghanistan, the highest ratio in any conflict in the history of the US.

The best known PMCs, Xe (Blackwater), DynCorp, MPRI (Military Professional Resources Inc) and Kellog Brown and Root (4), are all part of a grouping known as Private Security Companies of Afghanistan. Their involvement takes a big bite out of the funds intended for the reconstruction of the Afghan National Army (ANA).

Although they are supposed to play an auxiliary role to the coalition, and to the US army, the legal status of the PMCs is vague. But behind the “turnkey” solutions they offer lie big business interests, which influence military decisions in the field. There is a convergence of financial interests between the PMCs and big US industrial conglomerates: most PMCs have been bought up by conglomerates through mergers and acquisitions, many since 2001.

Moreover, the boom in outsourcing coincides with the need of the US military to assure their own redeployment: most of the senior management of the PMCs are former military officers, who find it easy to make the transition from the public to the private sector. Former senior officers of US armed forces working for PMCs enjoy a close relationship with the Pentagon, which gives them easy access to classified information and guarantees a degree of impunity.

A British contractor said recently that the Americans, the British and other armed forces were in Afghanistan to win the war, but for his firm, the more the security situation deteriorated the better (5). This is not necessarily compatible with conflict stabilisation and the “Afghanisation” of peace.

Thanks to their manpower, their representation at the headquarters of inter-allied organisations and their international connections, the PMCs are in a position to influence military decisions on operational matters. Employees of MPRI (6) can be found throughout the hierarchy of ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) and the Afghan security forces. They serve as mentors to armed forces general staff and to governments, help to draft doctrine for the ANA as part of the Combined Training Advisory Group (CTAG), train officers at the Kabul Military Training Centre (KMTC) and provide instruction to specialists.

With in-depth knowledge of the Afghan theatre from tours of duty lasting two to four years, PMC personnel have unrivalled experience of local conditions. Their experience is a vital asset to the inter-allied staff officers whose tours of duty are rarely longer than six months. It allows them to co-ordinate, regulate and even promote the involvement of other PMCs and to steer the perceptions of the military in any direction that suits them.

According to official sources in the French ministry of defence, the budget allocated to MPRI for drafting the ANA’s military doctrine is some $200m; the training of ANA troops will cost nearly $1.7bn. So the PMCs have no interest in stabilising the situation or in the successful Afghanisation of the ANA. That would lessen the need for contractors, which would be against their financial interests. So they take great care not to pass on their knowledge, and prefer to deputise for Afghan organisations rather than giving them useful advice.

Solidarity among PMCs

“General” Gulbahar, in charge of doctrine at the Afghan National Army Training Command’s doctrine office, says he has been given no target date for the handover of the drafting of ANA military doctrine to Afghan control. Gulbahar is not unhappy to be supervised: he is in fact a colonel serving in a position normally occupied by a general and has everything to lose by questioning the status quo.

MPRI, therefore, has what amounts to a monopoly on the drafting of Afghan army doctrine, which allows it to justify the prolongation of its assisting role. But MPRI also shows solidarity with other PMCs: the ANA’s logistical doctrine, drafted by MPRI, names DynCorp as the organisation responsible for providing logistics support to the ANA’s air corps, without specifying any restrictions or limitations on the duration of this role.

The “training” element is highly profitable. The PMCs are recruiting and training 800 instructors as part of a programme to combat illiteracy in the ANA, but their determination to secure the greatest possible return on investment has encouraged them to extend the duration of the training provided. It would seem that fostering the ANA’s own training capabilities is not a priority. The same applies to logistics (currently provided by RM Asia), another key element of the PMC monopoly: no deadlines have been set for the training of Afghan technicians.

Here again, the financial interests of the PMCs, which employ several thousand contract staff, differ from the military interests of ISAF: but they do not wish to see operational systems change too rapidly any more than they hope for a swift victory. They need to be able to influence events and, if necessary, to steer policy at the operational and strategic levels.

New opportunities

They will soon have a new opportunity to consolidate their position. Brigadier Neil Baverstock, the British commander of CTAG (located near Kabul), has launched a drive to systematise the training provided to ANA units by public and private instructors. This development will lead to greatly increased demand for instructors and open up new opportunities for the principal contractors, who are already planning to use in Afghanistan the manpower and resources no longer needed in Iraq.

New contractors have recently been recruited to draw up “return of experience report” (retex) procedures for the ANA. The precious information gathered from retex reports will give the PMCs an overview of the theatre and the opportunity to consolidate their strategic position in the drafting of doctrine for the ANA as well as in its training.

As in Iraq, the use of “rent-a-soldier” companies is undermining the credibility of international armed intervention. You only have to drive through the streets of Kabul to see this is so. The provocative, aggressive behaviour and attitude of some PMC personnel, and the equipment they carry, are disturbingly like the caricature action heroes of Hollywood films (portrayed by Arnold Schwarzenegger etc). The effect is devastating: “People in Afghanistan can’t tell the difference between ISAF soldiers and contractors,” says a member of the Afghan parliament. “The two are easily confused and this does not do the coalition any good since the ‘private soldiers’ are often very aggressive in their behaviour.”

How can efforts to put down an insurgency be effective or credible when the countries contributing to the intervention force, and representing the UN, use mercenaries whose motivation is not necessarily the restoration of peace? There are questions about the ethics of contractors and how safe it is to use them. More than half of the interrogators and all of the interpreters implicated in the Abu Ghraib scandal were recruited “externally” and worked for CACI International or Titan. The scandal revealed a complete absence of the military ethic among PMCs. PMCs do not operate within the same legal framework as state armed forces and are sullying the image of ISAF among the people of Afghanistan. It’s another question raised by the transition from the outsourcing of services to the outsourcing of war.

Marie-Dominique Charlier was political adviser to the commander of ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) in Afghanistan from February to August 2008 and is a researcher at IRSEM (Strategic Research Institute of the Ecole Militaire), Paris

(1) See Sammi Makki, “Silence of a very grand grave”, Le Monde diplomatique, English edition, November 2004.

(2) According to a study by the Congressional Research Service quoted by Walter Pincus in the Washington Post, 16 December 2009.

(3) In 2007 the US Department of Defence deployed up to 185,000 contractors in Iraq, as compared with 160,000 regular troops.

(4) Formerly a subsidiary of Halliburton.

(5) René Ourdant, “Les mercenaires mettent le cap sur l’Afghanistan”, Le Monde, Paris, 21 August 2009.

(6) MPRI, a division of L3 Communications, was founded by generals Carl Edward Vuono, former chief of staff of the US army during the first Gulf war, and Harry Edward Soyster, a former director of US military intelligence. The company employs more than 300 former generals.

http://mondediplo.com/2010/02/08afghanistan

A worrying two-thirds of the Pentagon’s personnel in Afghanistan are private military contractors, unaccountable to military law or ethics, swaggeringly overbearing, and not in any hurry to help improve the poor security situation that assures their firms’ current and future profits

by Marie-Dominique Charlier

The Central Intelligence Agency hired staff from a private military company called Blackwater in 2004 as part of a secret programme to track down and assassinate al-Qaida leaders, according to the New York Times of 19 August 2009. The paper’s sources among current and former US government officials said that Blackwater had helped the CIA with planning, training and surveillance, for which it had charged several million dollars, but the programme had failed to capture or assassinate a single al-Qaida figure.

Blackwater changed its name to Xe Services following the controversy over its role in Iraq. Five of its guards escorting a US State Department convoy through Baghdad on 16 September 2007 were accused of shooting civilians in al-Nousour Square, killing 14 (the US count) or 17 (the Iraqi count). In spite of this blunder, and many others, the contractors headed for Afghanistan, where they have continued in the same manner. (The case against them was dismissed on 31 December 2009 owing to procedural errors; the US Department of Justice has decided to appeal against the decision.) On 5 May 2009 four employees of Blackwater/Xe (operating under the name Paravant) reportedly shot at a car in Kabul, killing at least one person and wounding four. On 7 January federal prosecutors in the US announced that two of the Xe employees had been charged with killing two Afghan men and wounding another. The opacity of their employment contracts has not allowed them to escape prosecution.

Private military companies (PMCs) (1) have evolved rapidly since they first appeared in the 1990s and now play a key military and economic role in armed conflicts. The global market for private military services is worth more than $100bn a year. This growth has been encouraged by drastic cuts in US army manpower at the end of the cold war and the decision under Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld (2001-06) to “rationalise” defence spending by outsourcing many of the not specifically military functions to the private sector. The aim was to circumvent Congress control and US public opinion, and also to allow greater flexibility in hiring contractors for clandestine operations.

High numbers

Estimates of the numbers of PMC personnel in Afghanistan vary from 130,000 to 160,000 (2), the second-largest deployment after Iraq (3), which it is set to overtake in the near future. The 30,000 extra US troops bound for Afghanistan could be accompanied by up to 56,000 additional contractor personnel. PMC contractors will then account for nearly two-thirds of all the Pentagon’s personnel in Afghanistan, the highest ratio in any conflict in the history of the US.

The best known PMCs, Xe (Blackwater), DynCorp, MPRI (Military Professional Resources Inc) and Kellog Brown and Root (4), are all part of a grouping known as Private Security Companies of Afghanistan. Their involvement takes a big bite out of the funds intended for the reconstruction of the Afghan National Army (ANA).

Although they are supposed to play an auxiliary role to the coalition, and to the US army, the legal status of the PMCs is vague. But behind the “turnkey” solutions they offer lie big business interests, which influence military decisions in the field. There is a convergence of financial interests between the PMCs and big US industrial conglomerates: most PMCs have been bought up by conglomerates through mergers and acquisitions, many since 2001.

Moreover, the boom in outsourcing coincides with the need of the US military to assure their own redeployment: most of the senior management of the PMCs are former military officers, who find it easy to make the transition from the public to the private sector. Former senior officers of US armed forces working for PMCs enjoy a close relationship with the Pentagon, which gives them easy access to classified information and guarantees a degree of impunity.

A British contractor said recently that the Americans, the British and other armed forces were in Afghanistan to win the war, but for his firm, the more the security situation deteriorated the better (5). This is not necessarily compatible with conflict stabilisation and the “Afghanisation” of peace.

Thanks to their manpower, their representation at the headquarters of inter-allied organisations and their international connections, the PMCs are in a position to influence military decisions on operational matters. Employees of MPRI (6) can be found throughout the hierarchy of ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) and the Afghan security forces. They serve as mentors to armed forces general staff and to governments, help to draft doctrine for the ANA as part of the Combined Training Advisory Group (CTAG), train officers at the Kabul Military Training Centre (KMTC) and provide instruction to specialists.

With in-depth knowledge of the Afghan theatre from tours of duty lasting two to four years, PMC personnel have unrivalled experience of local conditions. Their experience is a vital asset to the inter-allied staff officers whose tours of duty are rarely longer than six months. It allows them to co-ordinate, regulate and even promote the involvement of other PMCs and to steer the perceptions of the military in any direction that suits them.

According to official sources in the French ministry of defence, the budget allocated to MPRI for drafting the ANA’s military doctrine is some $200m; the training of ANA troops will cost nearly $1.7bn. So the PMCs have no interest in stabilising the situation or in the successful Afghanisation of the ANA. That would lessen the need for contractors, which would be against their financial interests. So they take great care not to pass on their knowledge, and prefer to deputise for Afghan organisations rather than giving them useful advice.

Solidarity among PMCs

“General” Gulbahar, in charge of doctrine at the Afghan National Army Training Command’s doctrine office, says he has been given no target date for the handover of the drafting of ANA military doctrine to Afghan control. Gulbahar is not unhappy to be supervised: he is in fact a colonel serving in a position normally occupied by a general and has everything to lose by questioning the status quo.

MPRI, therefore, has what amounts to a monopoly on the drafting of Afghan army doctrine, which allows it to justify the prolongation of its assisting role. But MPRI also shows solidarity with other PMCs: the ANA’s logistical doctrine, drafted by MPRI, names DynCorp as the organisation responsible for providing logistics support to the ANA’s air corps, without specifying any restrictions or limitations on the duration of this role.

The “training” element is highly profitable. The PMCs are recruiting and training 800 instructors as part of a programme to combat illiteracy in the ANA, but their determination to secure the greatest possible return on investment has encouraged them to extend the duration of the training provided. It would seem that fostering the ANA’s own training capabilities is not a priority. The same applies to logistics (currently provided by RM Asia), another key element of the PMC monopoly: no deadlines have been set for the training of Afghan technicians.

Here again, the financial interests of the PMCs, which employ several thousand contract staff, differ from the military interests of ISAF: but they do not wish to see operational systems change too rapidly any more than they hope for a swift victory. They need to be able to influence events and, if necessary, to steer policy at the operational and strategic levels.

New opportunities

They will soon have a new opportunity to consolidate their position. Brigadier Neil Baverstock, the British commander of CTAG (located near Kabul), has launched a drive to systematise the training provided to ANA units by public and private instructors. This development will lead to greatly increased demand for instructors and open up new opportunities for the principal contractors, who are already planning to use in Afghanistan the manpower and resources no longer needed in Iraq.

New contractors have recently been recruited to draw up “return of experience report” (retex) procedures for the ANA. The precious information gathered from retex reports will give the PMCs an overview of the theatre and the opportunity to consolidate their strategic position in the drafting of doctrine for the ANA as well as in its training.

As in Iraq, the use of “rent-a-soldier” companies is undermining the credibility of international armed intervention. You only have to drive through the streets of Kabul to see this is so. The provocative, aggressive behaviour and attitude of some PMC personnel, and the equipment they carry, are disturbingly like the caricature action heroes of Hollywood films (portrayed by Arnold Schwarzenegger etc). The effect is devastating: “People in Afghanistan can’t tell the difference between ISAF soldiers and contractors,” says a member of the Afghan parliament. “The two are easily confused and this does not do the coalition any good since the ‘private soldiers’ are often very aggressive in their behaviour.”

How can efforts to put down an insurgency be effective or credible when the countries contributing to the intervention force, and representing the UN, use mercenaries whose motivation is not necessarily the restoration of peace? There are questions about the ethics of contractors and how safe it is to use them. More than half of the interrogators and all of the interpreters implicated in the Abu Ghraib scandal were recruited “externally” and worked for CACI International or Titan. The scandal revealed a complete absence of the military ethic among PMCs. PMCs do not operate within the same legal framework as state armed forces and are sullying the image of ISAF among the people of Afghanistan. It’s another question raised by the transition from the outsourcing of services to the outsourcing of war.

Marie-Dominique Charlier was political adviser to the commander of ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) in Afghanistan from February to August 2008 and is a researcher at IRSEM (Strategic Research Institute of the Ecole Militaire), Paris

(1) See Sammi Makki, “Silence of a very grand grave”, Le Monde diplomatique, English edition, November 2004.

(2) According to a study by the Congressional Research Service quoted by Walter Pincus in the Washington Post, 16 December 2009.

(3) In 2007 the US Department of Defence deployed up to 185,000 contractors in Iraq, as compared with 160,000 regular troops.

(4) Formerly a subsidiary of Halliburton.

(5) René Ourdant, “Les mercenaires mettent le cap sur l’Afghanistan”, Le Monde, Paris, 21 August 2009.

(6) MPRI, a division of L3 Communications, was founded by generals Carl Edward Vuono, former chief of staff of the US army during the first Gulf war, and Harry Edward Soyster, a former director of US military intelligence. The company employs more than 300 former generals.