The Continuing Aims of Zionist Policies in the Middle East

Israel Shahak

Dr. Shahak is Professor of Chemistry at Hebrew University and

President of the Israeli League for Human and Civil Rights. He is a

survivor of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. The purpose of this

article is to investigate the real aims of Zionist policies in the

Middle East (not only or even chiefly in relation to the Palestinians)

and the inevitable consequences of the support, whether intentional or

not, by the United States of those aims over a long period of time.

The reason for using the expression "Zionist policies" in the title is

to draw the attention to the remarkable fact that the present Israeli

establishment continues to pursue with remarkable constancy policies

which began around 1917-22. Also, from that time up to the present,

there has been a remarkable continuity in the actual composition of

the ruling establishment. In spite of the many and frequent changes of

the government and of the ruling parties, the new wielders of power

have always been people who spent long years serving the previous

regimes in military or political capacities, and presumably accepting

the majority of their policies. This includes all of the more

important politicians of the Likud. Yitzhak Shamir was for sixteen

years in Mossad (Israel's Secret Service) under Ben Gurion and Levi

Eshkol; Ariel Sharon was a favorite of Ben Gurion. Menachem Begin, as

the head of the major opposition party, for many years was informed of

everything and in return gave his loyal support to most of the foreign

policies of Israel. Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Rabin played the same

game from 1977-84, even during the 1982 invasion of Lebanon. In fact,

with the exception of small groups on the right and the left margins

of the political spectrum, Israeli foreign policies, like the Zionist

policies before them, have been governed by a consensus (as it is

called in Israel) which has endured now for more than sixty years,

during which time the cohesion of this basic unity has very rarely

been shaken or even threatened. The Zionist establishment is in fact

the oldest in the Middle East, for its continuity has never been

broken, either by a revolution or by a large-scale influx of persons

with a different education or outlook from the founding fathers'.

During the same period, all Arab countries experienced one or both of

these disruptive phenomena.

This long continuity is one of the most important components of

Israeli strength. But the resulting inertia and reliance on old

precedents is also a source of weakness, particularly when new

policies or new approaches have to be devised. In particular, Israeli

policymakers will usually view the Arab world from a static point of

view and try to ignore the changes, particularly the social changes,

taking place in it.

As this analysis is concerned with long-term aims, I will ignore the

differences among "hawks" and "doves" within the Israeli

establishment. These are less significant than outsiders suppose and

are concerned mainly with means rather than ends. For example, many of

the Israeli establishment "doves" opposed Sharon in 1982 because they

were of the opinion that a much greater military effort should be

mounted against the Syrians, or that the alliance inside Lebanon

should not have been made with Phalangists, or not exclusively with

them. They were especially divided over how to represent the war to

the Israeli public or to world opinion. War itself was very little

opposed from inside the Israeli military establishment, although

everybody knew that it was coming. In a similar way in 1956, the

leftist opposition within the establishment opposed the Israeli

alliance with Britain and France but was of the opinion that Israel

should have attacked Egypt without them and changed the regime there.

In the same way, the Israeli attacks on Jordan in 1966-67 and the

attacks on the Syrian airforce over Damascus airspace ("in order to

change the Syrian regime" as Yitzhak Rabin, then the Chief of Staff,

proudly declared) which led to the six day war were supported by the

whole Israeli establishment. Of course, within this concensus there

are numerous pragmatic disagreements, but for the purpose of

discovering real long-term aims they can be ignored. Those aims can be

discovered first, from activities of the Israeli government; second,

from declarations obviously intended for the internal consumption of

the Israeli establishment itself; and third, from the rich historical

literature in Hebrew dealing with the history of the last sixty to

eighty years, some of which is on a very high level of veracity and

scholarship.

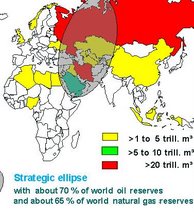

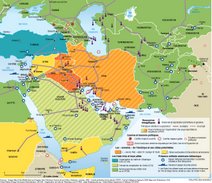

DOMINATION OF THE MIDDLE EAST

It is quite clear that the domination of the whole Middle East by

Israel is the constant aim of Israeli (and before this of Zionist)

policies and that this aim is shared (within the establishment) by

both "doves" and "hawks." The disagreement is about the means: whether

by war -- carried out by Israel alone or in alliance and on behalf of

stronger powers -- or by economic domination. This can best be shown

not so much by the case of the Palestinians, where the immediate

expropriation may obscure the wider thrust of policy, but in the cases

of Egypt, Syria and even Iraq. As early as the 1920s, all the

influence of the Zionist pressure-block in Britain was pitted against

the Egyptian National Movement, led then by Zaglul Pasha and the Wafd

Party. Both Chaim Weitzmann and Vladimir Jabotinsky opposed what they

called "British concessions" to Egyptians.

An important part of the argument about the long-term Zionist aims is

the fact that the opposition of Weitzmann, the supposed "dove," was

actually stronger and more adamant than that of Jabotinsky, who is

usually considered a hawk. Weitzmann opposed every Arab movement,

based -- as was inevitable and natural in the twenties -- on the

rising Arab middle class, and he did this by propagating among his

British friends a type of anti-Arab racism which can only be compared

to Nazi anti-Semitic outbursts. For exmaple, Weitzmann wrote to

Balfour on May 30, 1918:

The Arabs, who are superficially clever and quick-witted, worship one

thing and one thing only, power and success. . . . The British

authorities, . . . knowing as they do the treacherous nature of the

Arab, have to watch carefully and constantly that nothing should

happen which might give the Arabs the slightest grievance or ground of

complaint. In other words, the Arabs have to be "nursed," lest they

should stab the army in the back. The Arab, quick as he is to gauge

such a situation, tries to make the most of it. He screams as often as

he can, and blackmails as much as he can. . . . The fairer the English

regime tries to be, the more arrogant the Arab becomes.

(quoted from the original files of the British Foreign Office in

Publish It Not: the Middle East Cover-Up, by Mayhew and Adams,

Longman, 1975).

The Zionist, and later the Israeli, policies of opposition to every

step on the road to Egyptian independence, backed at least in private

by arguments of a similar type, continued to the point of formal

demands made by the newly created State of Israel to Britain not to

remove its troops in the early fifties from the canal zone. The

notorious "Lavon affair," in which an Israeli spy ring based on

members of the Jewish Egyptian community tried to put bombs in

Egyptian cinemas or in the American Library there, was similarly

intended to prevent the evacuation of the British troops from Egyptian

territory and to create the impression that the Egyptians are

terrorists, a theme which is still used about the whole Arab world.

Similarly, the aim of the 1956 Suez war from the Israeli point of view

was not only the destruction of the Egyptian army or the annexation of

Sinai, but the change of the Egyptian regime of that time. In fact,

Lova Eliav, then and now one of the leaders of the Israeli doves,

headed, by his own subsequent admission in 1972, a special task group

which was intended, in cooperation with the French government and

support from within the then-existing Jewish community of Cairo, to

carry out a coup d'etat and put into power politicians whom Israel

thought reliable. The plan was only prevented, to the great regret of

Israeli "doves," because it was made behind the back of the British

government of that time, which discovered it at the last moment and

vetoed it.

Through this whole long period from the twenties, the Zionist movement

and Israel were indeed in contact -- sometimes very intimate contact

-- with Egyptian politicians who were prepared to undertake policies

which would have entailed the continuation of Egyptian dependence on

outside powers and its separation from the rest of the Arab world as

the price of support for themselves. This aim was only achieved by

Begin's alliance with Sadat, which continued long-term tendencies,

with the United States being substituted for Britain and France. This

was made clear in 1977-1978 inside Israel, when the real compensation

for the Israeli withdrawal from Sinai was explained as being "the

drawing of a wedge between Egypt and the rest of the Arab world," and,

even more important, making Egypt completely dependent on yearly

financial support from the U.S. Congress, where Israel holds virtual

veto power, a sort of sword of Damocles over Egyptian policy.

One can say that the major difference between the so-called "doves" of

the Israeli establishment and the real radical opposition is with

regard to this policy. The establishment "doves" not only support it

but consider that it can be made into a permanent situation, while the

anti-establishment radicals understand that ultimately such policy is

self-defeating in terms of Egyptian society because it increasingly

alienates the Egyptian government which tries to carry it out. In

addition, the American aid, over which Israel has a veto power, must

be of such nature as to prevent any real development of Egyptian

economy or society, as has indeed happened.

A very good recent example of this constant attitude can be found in

the September 1985 issue of New Outlook, widely considered to be a

"peace journal," in an interview with Professor Shimon Shamir about

the Israeli achievements in Egypt made possible by the Camp David

agreement and the Israeli-Egyptian peace. In the opinion of Professor

Shamir, an Israeli Arabist with great influence on the government, one

of the Israeli achievements is that the Egyptian army is occupied now

with the construction of roads and buildings and even the baking of

bread. In other words, since it undergoes little military training, it

is a weak army. Can a state with a very weak army be called truly

independent? Can the majority of a people desire, or long tolerate, a

bread-baking army? We will return to a deeper consideration of these

questions after considering Zionist policies toward other Arab

countries.

An even better example is the now-revealed affair of Israeli relations

with the Syrian regime of Husni Zaim in 1949-50. That very unstable

and narrowly based regime wanted desperately to acquire American

support, and thought that it could do so by offering to "solve" the

Palestinian "problem" in the interest of Israel, by settling all the

Palestinian refugees in the Syrian territory beyond the Euphrates --

that is, as far away from Palestine as possible. The scheme was

vigorously pursued until the very moment when Husni Zaim was

assassinated. A high-level CIA dignitary was actually present in

Damascus at the time of the assassination to serve as a messenger from

the Israeli government, according to a report released from the

Israeli archives in accordance with the thirty-year rule of secrecy.

But the most illuminating part of that affair, as it affects present

Israeli policies, is the manner and the reason for its publication in

spring 1985. It was published in Al Hamishmar, the paper of the Mapam

Party (now formally in opposition, but really a part of the

establishment), as part of an argument against Ben Gurion, who did not

pursue, in the opinion of the "dovish" author, this scheme as fast as

he should and so missed the opportunity for peace. I am passing over

the Palestinian aspect of this scheme as being clear enough. But what

about the assumption of the Israeli "doves" about Syria or the rest of

the Arab world? It is obvious that any Syrian government which

attempted to carry out such a policy would have become alienated from

its own people, and thus completely dependent on the outside support

of Israel and the United States. Even with such support, of whatever

magnitude, it could not endure for long.

But for Israeli establishment "doves," this elementary point cannot be

grasped, even now. Israeli policy towards Syria can only be

comprehended if one understands the social fact that the whole Israeli

establishment, "doves" included, not only believes in making "deals"

-- such as the one described above -- with Arab regimes but also

disregards the certainty that regimes which consent to such deals will

become as alienated from their own people as the "Village Leagues" in

the West Bank or the "South Lebanese Army" are at present.

To cite a further example, in 1930-32 the Jewish community of Baghdad

was incited to oppose, openly and formally (but unsuccessfully) in

petitions to the British government and the League of Nations, the

change of status of Iraq from a mandate to a formally independent

country. The expulsion of Jews from Iraq in the early fifties is now

known, from reports released from Israeli archives, to have been

carried out with the full cooperation of Israeli agents who were

established in Baghdad at the time and who not only negotiated with

the Iraqi government and with the real ruler of the country, Nuri

Said, but actually boasted in a telegram sent to Tel Aviv that they

were "cooking more quickly" the law expelling the Jews from Iraq. The

"quick cooking" involved anti-Iraqi activities in the United States in

which American Jews took a prominent part. It seems that the Israeli

influence on Iraqi policies in the period before 1958 was quite deep

and extensive, and was probably one of the reasons for the fall of the

regime.

These are examples of activities which were not condemned within the

Israeli establishment when they were published in recent years,

despite the deep intervention in Lebanon. Many similar discussions

about proposals from the same period made both by "doves" and "hawks"

could be quoted to illustrate the thesis that the domination of the

whole Middle East, either by a warlike conquest of parts of it or by

alliances with regimes which necessarily become alienated because of

such alliances, or by making those regimes dependent on an internal

power structure over which Israel (or the Zionist movement) has a

great influence, has been and remains the real Israeli aim. In

pursuing this aim the Israeli establishment has shown both flexibility

and tenacity in the methods employed, and also in being ready to make

significant retreats when under compulsion.

There are two principal examples of such retreats: the retreat from

Sinai from 1956-57, made because of the insistence of the two

superpowers, and the retreat from most of the area of South Lebanon,

made under the pressure of popular resistance. The lesson of 1956-57

has been absorbed by the Israeli establishment. All possible efforts

have been made (and will be made) to prevent any cooperation between

the United States and the USSR on Middle Eastern affairs, with great

prospect of success in that direction. The lesson of guerrilla warfare

based on popular support in Lebanon in 1983-85 has not been absorbed

in Israel. In fact, the profound social change which has occurred in

most Arab countries since the fifties is not understood. The inertia

resulting from long continuity produces the effect that the only

"model" of an Arab regime (or movement) which the Israeli

establishment -- the "doves" particularly -- assumes and wants, are

such as were only too prevalent from the twenties to the fifties, and

whose most characteristic feature was dependency on outside powers

combined with alienation at home. Sadat of the last few months of his

life fit the model perfectly.

JUSTIFYING "PREVENTIVE" WARS

The invasion of Lebanon in 1982 and the subsequent Israeli opposition

to that war have created in some circles outside Israel a false

picture of a change within the Israeli establishment which did not

happen. Since I am describing here the mainstream of Israeli opinion,

I will ignore the radical opposition to the war to concentrate on one

aspect of the debate within the establishment. Sharon and his henchmen

were accused, time and again, of deceiving the Israeli government and

the public as to the extent and the firepower of the PLO armed forces

and the Syrian units in Lebanon. Sharon claimed that they were huge

and so had to be destroyed because the very existence of such a

military force is a "reason" for an Israeli attack. His establishment

opponents, who were factually correct, said that the PLO and Syrian

armed forces in Lebanon were small. Both sides actually shared the

same assumption, which dates from the early fifties, that the very

existence of an Arab state with a military force, beyond certain

debatable qualitative and quantitative bounds, is a "reason" for an

Israeli preventive attack on it. Consideration of parity between

Israel and the other state is out of the question.

It is extremely important to understand that this fixed policy is now

propagated with full force as the reason" for the next Israeli

preventive war. There has been a whole series of very serious

predictions from the highest military sources (from October 1984) that

war with Syria is "inevitable." On June 10, 1985, Tali Zelinger, the

military correspondent of Davar, announced in the name of the

"security apparatus" (the army together with the various intelligence

systems) that "the evaluation today is that sooner or later a war

between Syria and Israel will break out." Even more open was Ran

Edelist, the military correspondent of Monitin, the most prestigious

Hebrew monthly, in the August 1985 issue (which appears at the end of

July). To explain better what he did and how the Israeli establishment

can find ways to circumvent censorship in order to show to its members

which way the wind is blowing, it is necessary to explain that

subtitles of articles in the Hebrew press do not have to pass the

censor but are added by the author or the editor at the last moment.

Ran Edelist, who enjoys the best contacts with Israeli generals,

interviewed first a colonel in the reserves, Haim Yaabetz, who has

just retired from long and distinguished service in military

intelligence which included in its last years strong support for the

"strategic megalomania of Arik Sharon." He then added to the

interview, which proceeded along the usual lines of the inevitability

of war (not only with Syria, but as a permanent characteristic of

Israeli existence in the Middle East) the following subtitle quite

unconnected with the text:

Division commander in the North, D., ordered his officers to make

known to all soldiers of this division that the war with Syria is very

near, and I, a red-haired brigade commander, told all comrades: ‘This

is what is going to be, this is what exists, so let us fall to work'.

The author then discusses in considerable detail "the price" in number

of victims that Israel is going to pay for its future victory over

Syria. I emphasize that such announcements, especially those made to

officers by division or brigade commanders in Israel, are to be

regarded very seriously, since it is by such means that the real

decision makers in Israel (who are not the government, which is

informed at the last moment) communicate their decisions to the most

important part of the Israeli establishment. The real decisions to

attack Egypt (in 1956) or to invade Lebanon (in 1982) were

communicated in exactly the same way. In 1967 although Nasser's steps

hastened the process, the officers knew that Israel was going to

attack weeks before it happened, while the majority of the Israeli

government fondly imagined that war could yet be averted.

Of even greater importance are the clear signs in the Hebrew press and

other Israeli sources which predict an Israeli attack on Jordan.

Again, if we will free our minds of cant and of the influence of

Israeli official propaganda and take a hard look at Israeli actions

through the years, we will see that the actual type of an Arab regime

(monarchical or republican, "right" or "left") is of no importance to

Israel. What is important is whether it is strong or weak militarily

and otherwise, and whether it enjoys a measure of popularity with its

subjects. A Middle Eastern Arab state which is developing military

strength is going to be attacked for this very reason (when the

conditions are favorable), and those interested in Middle Eastern

politics should accept this high probability as a fact of life, until

it is altered by a basic change within the Israeli Jewish society. Let

me quote rather extensively from the Hebrew press, which, as usual,

explains this in advance to its readers. Reuven Padahtzur, the

correspondent of Haaretz on military affairs and one of the most

serious and better informed writers on that subject in Israel, writes

under the title "Who Wants a Preventive Blow?" (Haaretz, July 4,

1985):

Supplying the Jordanian army with advanced fighter planes and mobile

land-air missiles might force Israel to react with a preventive blow

in the case of a war breaking out in the region. The American-

Jordanian arms deal must be considered not only from the relatively

narrow viewpoint of direct military risks emanating from the supply of

modern, sophisticated weapons to the Jordanian army. One of the

interesting, dangerous and undesirable repercussions of this

transaction is the almost total limitation of the variety of military

options that the Israeli Defense Army will have. The introduction of

advanced fighter planes and of mobile land-air missile batteries into

Hussein's army might force Israel to react in advance with a

preventive blow against this army, in every case of war breaking out

in the region.

After giving in great detail the military equipment which Jordan has,

or is going to purchase mainly from the United States but also from

the USSR, and after highlighting the great danger to Israel from the

"joint maneuvers by the Jordanian and American forces," since those

exercises are an important contribution to the improvement of the

offensive capacity of the Jordanian army, the author concludes:

Israel's security policy must have an answer also for the worst

scenario. One of these scenarios, taking into account a situation when

Israel has to face the outbreak of war on the eastern front, including

the armies of Syria, Jordan, as well as Iraqi expeditionary

contingents, forces the Israeli Defense Army to take immediate steps

in order to neutralize the threat to sensitive targets inside Israel.

For this purpose it seems that there will be no choice but to inflict

a preconceived preventive blow on Jordan.

Thus, paradoxically, the supply of modern sophisticated weapons to the

Jordanian army not only does not enhance the security of the Kingdom

of Jordan, but even involves a great danger to its army (my emphasis).

The same theme was taken (among many others) by the famous Zeev

Schiff, also in Haaretz (August 16, 1985) in an article entitled "Who

Wants to Finish Off Hussein?" After pointing out that the old, well-

known plan of Sharon for what he calls "a Palestinization of

Jordan," (which means an Israeli conquest of Jordan and an

establishment of a "Palestinian" regime there of the "Village League"

variety) has also been supported for many years by some Israeli

leaders of the Labor Party, he describes the ways in which a "case"

for such a step will be built in Israeli public opinion (and a part of

American opinion as well, one may add):

One does not begin with sudden (airforce) bombardments in the center

of Amman. Also in Lebanon it did not begin with the invasion itself

and the military advance on Beirut. Before this, "the case" should be

built, the threat should be cultivated, until it becomes something

insupportable as a threat to existence, in the eyes of (Israeli)

public opinion (my emphasis).

He even hints at further very interesting possibilities: After

pointing out that "the modern history of the Middle East is full of

examples of removing a ruler by means of murder" and that King Hussein

was a target for such attempts in the past, he sagely observes that in

the past, "those who indulged in such machinations were always Arabs,

but it should not be so in the future. Different scenarios are

possible in such a situation. If someday the responsibility for the

Israeli Intelligence and Security Services falls into the hands of a

person without restraint, everything is possible" (my emphasis). As we

say in Hebrew, a hint to the wise is enough, and here we have much

more than a hint; we have a full scenario which is not dependent,

except in timing and outward presentation, on Sharon becoming once

more the power inside the Israeli government, but on the same basic

reasons which have ruled Israeli (and before this the Zionist)

policies for a long time. Incidentally, Schiff quickly adduces as the

"reason" which worries Sharon and pushes him to advocate an Israeli

"preventive" attack on Jordan, "that a part of the PLO is becoming

more moderate." In this there is also nothing new; the careful

observation of the cease-fire by the PLO between August 1981 and June

1982 was one of the reasons, freely admitted inside Israel, why Israel

invaded Lebanon. This is part of a familiar pattern.

I will only briefly mention the "reasons" which are being given to the

more gullible parts of public opinion, especially in the United

States, for such scenarios: "The fight against terror," particularly

world terror, is one of the most important of them, and of course

protecting "Western civilization," as has been said countless times in

the past. Here, too, nothing changes. Indeed the main point of this

article is that the policies of the Zionist and Israeli establishment

are, so far, constant, and therefore an unprejudiced analysis of the

past can be a guide to the contingencies of the future.

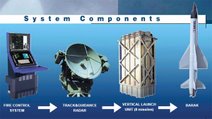

This analysis can be confirmed by an examination of the official

"reasons" put forth inside Israel for the present "missile conflict"

with Syria. Briefly, Israel claims for itself the right to dictate

where, on its own territory, Syria will or will not station weapons

(even such defensive weapons as anti-aircraft missiles). It is

important to perceive that all public opinion in Israel, except the

opposition from the left to the present National Unity government

(about 13 percent of the political strength as expressed by Knesset

seats), is united on this point. The whole debate, as freely expressed

in the Hebrew press (not in the Jerusalem Post, of course), is whether

Israel should first take the diplomatic road and only afterward attack

Syria, or attack without diplomacy at a time of its own convenience.

The principle of domination -- that Israel can unilaterally dictate to

an independent state about defensive weapons on its own territory --

is accepted by a great majority of the Israeli public, including,

contrary to the myths propagated among both the Western and the Arab

publics, the "Peace Now" movement. Nor is this the first demand of its

kind. On the contrary, like the political demands discussed above, the

demand that the Arabs disarm or limit their armaments goes back to

1918-20, and continues throughout Zionist history. To limit discussion

only to the last few years: 1) the overflights of the Saudi bases like

Tabuk, which reinforced the Israeli demand that Saudi planes or other

equipment should not be based there, and 2) the demands to limit the

sales of sophisticated defensive weapons to Jordan and countless

others are of exactly the same kind and illustrate the same principle

of domination of the whole Middle East which not only Israeli

governments (and before them the Zionist leadership) but the great

majority of the Israeli public support as a principle of such

overwhelming importance that it justifies waging a war.

It is even more important to perceive that the United States now, like

Britain and France before it, agrees in principle to those

imperialistic Israeli policies and only tries to soften them in their

practical application. American diplomats carried the Israelis'

demands (which by any standard, whether that of international law or

the principle of self-determination, were outrageous) to Syria in the

winter of 1985-86, as they carried similar demands to Saudi Arabia

before. The American government and an overwhelming part of public

opinion, as expressed in the media, accept without discussion the

"principle" that Israel can dictate through the United States to Arab

states, but not of course the reverse. It is acceptable to the

American Congress that a discussion of national dimensions should be

held about whether AWACS planes in Saudi Arabia are a danger to

Israel, but there is no record of any discussion in the Congress over

whether any of the many types of offensive weapons delivered to Israel

by the United States is a danger to any or all Arab states.

Of course, such "principles" are used, and have been used through the

ages, in relations between the superpowers and weaker states. But the

extraordinary and exceptional case of Zionism and Israel consists

exactly in this: that Israel by itself does not have the strength to

be a superpower dominating the Middle East, even through military

conquest. It employs to a great extent the strength of others, relying

on internal manipulation of the public opinion of the really strong

powers. This fact, however obscured in the Western media and unclear

(I think) to a great part of the pro-Western Arab establishments, is

quite clear to the Arab peoples. The diplomats can be, perforce,

satisfied with humiliating arrangements which achieve some small

measure of practical success, i.e. the Israeli flights over Saudi

territory cease after a time, or after a great dispute some old

Hercules planes are delivered by the United States to Egypt. But the

people, particularly the educated people, who are interested in

politics and determine it in the long run, feel the humiliating

principle involved and become -- indeed must become -- more and more

alienated from their pro-American regimes and also more anti-American.

As I have tried to show, this has also been one of the constant aims

of Zionist and Israeli policies. The effect of these popular pressures

in Arab countries, whether expressed in demonstrations and protests or

in individual acts of indiscriminate terror which have a measure of

popular support, is the same. I am not discussing here acts which I

condemn on moral grounds, but rather their social and political causes

and effects. A vicious circle is created in which precisely those

basic discriminatory anti-Arab principles of American policy are being

reinforced, and they in turn reinforce the alienation of the Arab

peoples from all pro-American regimes. No merely diplomatic solution

of any kind, no "peace process" can break this vicious circle so long

as the principles which the United States inherited from Britain and

France and which are constant in Zionist and Israeli policies, remain

unchanged and undiscussed. The present course of affairs will lead

necessarily to either another "ordinary" war or to a much bigger

conflict of catastrophic dimensions.

One relatively recent example of American policy in the Middle East

can illustrate the basic principles involved and their perception by

all the peoples of the Middle East (Jews as well as Arabs, only in a

contrary sense). I refer to the affair of the American intervention in

Sudan to help (by corruption, bribery and undue influence) the Falasha

Ethiopian Jews to come to Israel, where many of them were settled in

the West Bank despite some feeble official American protests, which

were treated by Israel with justified contempt. The facts are clear

enough, although widely disregarded by the American media: Sudan and

Ethiopia are full of starving refugees numbering many millions. In the

midst of this general human misery, an enormous American effort both

in money and politics, involving the Vice President of the United

States, was spent on helping a small group of people whose sole

criterion was that they were recognized as being Jews by the Jewish

State.

Politically, this effort was one of the main causes, perhaps the most

important immediate cause, of the fall of the Numeiri regime. The

trials, now continuing, of the highest Sudanese officials, followed by

all Middle East people with great interest, reveal to all of them the

fundamental principle of American (and of course Israeli) policy in

the Middle East: racist discrimination. Human suffering by itself does

not count; the most important, almost the only, criterion is to what

group of people the human being belongs. If he belongs to the group

considered superior (in a similar way to the superiority, assumed

fifty years ago about the "Aryans") then all the effort of the United

States will be spent on his behalf, even to the extent of harming the

immediate pragmatic interests of the United States. But if he belongs

to the millions of "inferior" people, to which all non-Jews of the

Middle East belong according to accepted principles of American

politics, then very little is owed to his human suffering and nothing

to his human dignity. The word "fanaticism" is very often on American

and Israeli lips where Arabs are concerned, but it should be

recognized that the Zionist and Israeli principles of policy with

regard to the Arab peoples of the Middle East are fanatical, both in

their total disregard for reason and social facts, and in their

application, which continuously defies most considerations of

political interest or "Realpolitik." Without this necessary

recognition of the blind fanaticism involved in the real Zionist and

Israeli policies and in the acceptance and internationalization of

this fanatical approach by the American establishment, no

understanding of the actual course of politics in the Middle East is

possible. With the acceptance of this as the main explanatory factor,

the actual course of affairs can be understood, both the past and as

far as possible the future as well.

APPENDIX: ON THE NECESSITY OF KNOWLEDGE, WHICH IS ALSO POLITICAL POWER

Professor Edward Said, in his most important work, Orientalism, has

pointed out how the mainstream of the Western "Orientalist" research

served, consciously or unconsciously, the aim of domination of the

Arab world by the Western powers. However, one should add to his

analysis one important factor: Orientalism was indeed a powerful

instrument of penetration and conquest because it contained useful

facts, however maliciously arranged, and also because the Arab world

was almost completely ignorant about the West. A corresponding

situation exists now: Israel and "Israeli friends" in the West are

well-informed about the Arab world, at least factually, even though

that information is usually arranged in the interest of Israeli

domination. On the other hand, an almost complete ignorance about

Israel prevails, as can be deduced from the fact that a serious and

comprehensive survey of the Hebrew press does not exist outside

Israel, certainly not in the Arab world. (Incidentally, one can say

that the ignorance of Palestinians, except those living in Israel,

about Israeli affairs is as great as that of the other Arab peoples).

Although, as has been implied above, this does not prevent these

peoples from perceiving the basic truth and from acting accordingly

after a period of time, it prevents the average Arab intellectual and

also the small minority of Western people who do not accept anti-Arab

fanaticism from analyzing the situation before it is too late. As

Francis Bacon said, knowledge is power; this applies also to political

knowledge. The accurate, factual and ideological knowledge of Zionism

and of Israeli society and politics is the most important single

condition for breaking the vicious circle of the attempted Zionist

domination of the Middle East. This domination is ultimately doomed to

failure, but in the absence of knowledge this failure will cost much

more in blood and human suffering than otherwise.